The 1960s

Throughout the 1960s, T-shirts continued to grow in popularity. Athletic wear companies that had included T-shirts in their catalogues since the 1920s quickly adopted printing technology to promote sports teams and create school varsity apparel. For children, T-shirts had proven to be ideal for rowdy excursions outside prone to making clothes dirty or damaged. The low cost of the T-shirt made it easily replaceable if it was to be ripped or stained. Commercially, the British Invasion of the early 1960s created an increase of band T-shirts made for fans to show off their favourite member of The Beatles and partake in Beatlemania. Later in the decade, this would set the stage for a cottage industry of music industry T-shirts. Quickly realizing the appeal to consumers of designing their own shirts, art supply stores and sporting goods stores began selling Do-It-Yourself (DIY) print screening kits.[1]

Background: Navigation signs on a tree at the Woodstock Music and Art Festival, 1969.

Kellogg’s cereal advertisement featuring a little boy wearing a T-shirt, 1964.

Fruit of the Loom advertisement targeting the older male demographic, who wore the t-shirt as an undershirt in the late 1960s, 1968.

Freedom Summer volunteers and locals canvas neighbourhoods in Mississippi, 1964.

The 1960s were an overlapping minefield of social revolutionary movements, created by the momentum of the Civil Rights Movement that had begun in the mid 1950s. Freedom Summer in 1964 attracted students nationwide to southern states to aid in voter registration.[2] Upon returning to their respective campuses in the fall, students were proud to show off their battle scars and tell stories from their intrepid missions.

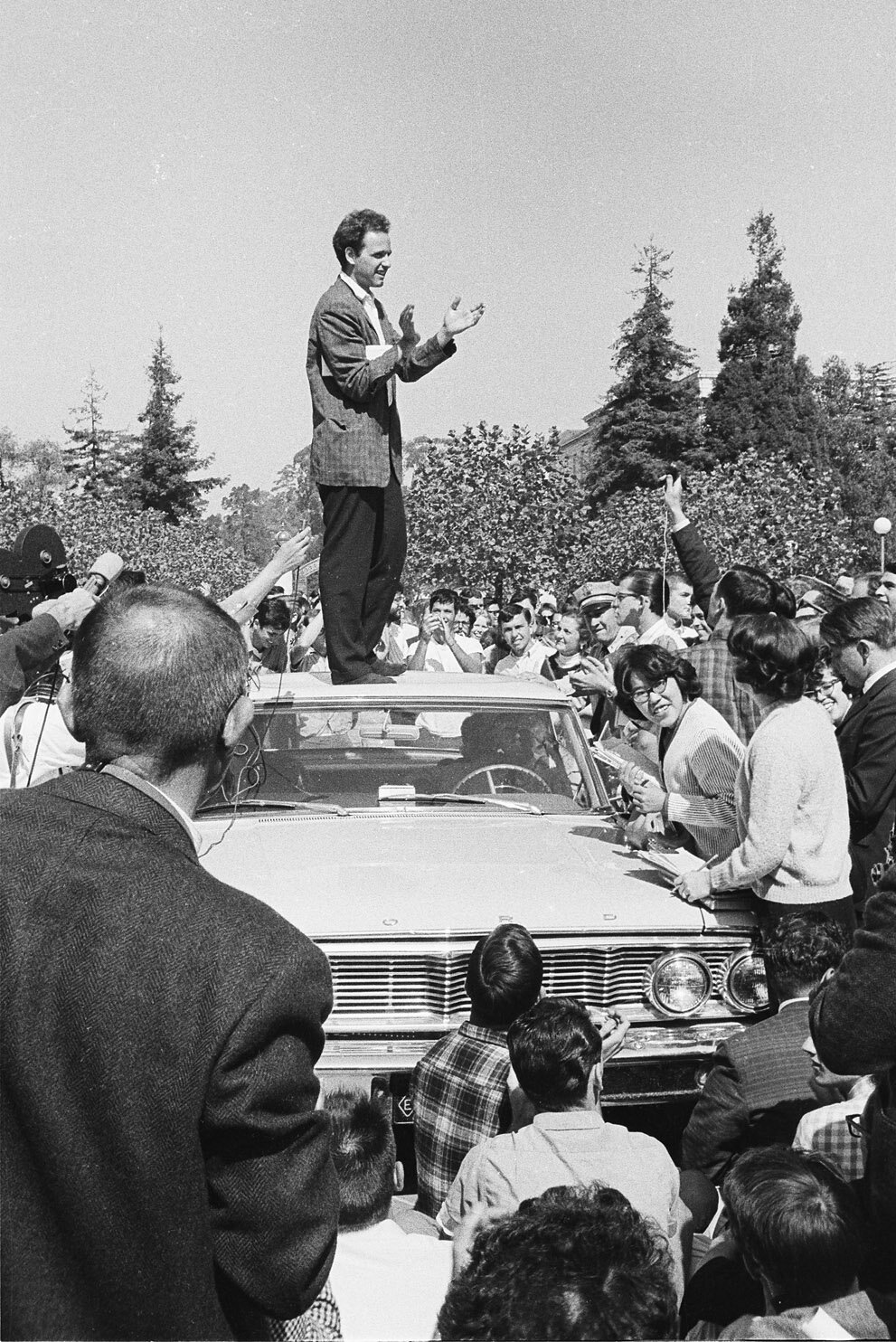

Mario Savio, student and CORE activist, speaking from the top of the police car holding Jack Weinberg. Oct. 1, 1964

At the University of California at Berkeley, graduate student Jack Weinberg was arrested while manning a booth for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) for violating the university’s policy against political activism. [3] Enraged and emboldened from their experiences over the summer, students mobilized. The Free Speech Movement began in the fall of 1964 and inspired campuses nationwide. Students now felt it was their civic duty to critique the authoritative powers that not only controlled campuses, but the nation as a whole.

Jack Weinberg, student and CORE activist, in the back seat of the police car. Oct. 1, 1964

The Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), formed in 1962, sought to enable students to speak freely about social and political issues. The SDS organized teach-ins, seminars and workshops that would run at night. Visiting scholars and intellectuals debated the ethical implications of American involvement in the war in Vietnam throughout 1964 and 1965.

As President Johnson initiated on the ground American involvement in 1965 through Operation Rolling Thunder, the division between pro and anti-Vietnam groups became more hostile.

Background: footage of Operation Rolling Thunder

The effects of the Vietnam War rippled throughout the country. The counterculture of the 1960s was a mass component of the anti-war movement, which included members of the Student Movement and Civil Rights Movement. The hub of the counterculture, the Haight Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, had witnessed a mass exodus of young people throughout the mid 1960s seeking solace from the tension that engulfed the rest of the country. Between 1965 and 1967, an estimated one hundred thousand people moved into the twenty five block area.[4] The draft had threatened the livelihoods of many not willing to put their lives on the line for a war they did not believe in.

The hippies of Haight-Ashbury believed they could solve the world’s problems through free love, peace and a considerable amount of psychedelic drugs. Hippie culture emphasized a rejection of the status quo that had restricted their parent’s generation,[5] and the unconventional nature of the T-shirt was a natural fit for this environment. The T-shirt was expected to be worn by men under a collared shirt, by children or for athletics. The act of wearing one casually in public, especially by a woman, was provocative.

Peggy Caserta, owner of hippie boutique Mnasidika in Haight-Ashbury, wearing a surfer-style t-shirt. Friend and leather smith Bobby Boles sits next to her wearing a sport-style T-shirt over a dark turtleneck. Late 1960s.

Young couple walking the streets of Haight Ashbury, 1967.

Similarly to the anti-war movement itself, the T-shirt had become considerably more revolutionary in just a few years. It was cheap and disposable, much like the draft cards that were burned at anti-war rallies across the country. T-shirts soon underwent a countercultural makeover, utilizing the Indian practise of bandhi to create psychedelic tie-dye t-shirts. DIY silk-screening and the new technology of heat transfer inks and papers created shirts that would be sold by hippie vendors in the streets of Haight-Ashbury and at music festivals. The baby boomer generation could now express political affiliations and musical preference through their T-shirts. [6]

The feeling of unconditional love and unity had faded dramatically by August 1968 when Democratic National Convention (DNC) convened in Chicago.

In the months leading up to the event, the US witnessed the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy. The true state of the Vietnam War, including the mass amounts of Vietnamese civilian casualties had finally come to light, and a general distrust of the White House and President Johnson had created a tense environment..[7] Several political groups had planned to be present in Chicago for the convention.

Background: Protestors clash with Chicago Police at the Democratic National Convention, Aug 1968.

Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin at the New York Stock Exchange following their act of theatrical protest, Aug 24, 1967.

Yippie poster advertising the Festival of Life, 1968.

One of these groups was the Youth International Party, also known as “Yippies”.[8] Guerilla theatre activists Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin wanted to create a phony social group to serve as a media focal point and parody of the counterculture. Hoffman and Rubin had become counterculture celebrities when they staged a theatrical protest at the New York Stock Exchange, raining single dollar bills onto the trading floor.

The Yippies were created in New York City on New Year’s Eve, 1967. Greenwich Village had evolved into the eastern counterpart to Haight-Ashbury, often replicating events from the west coast three to six months later.[9]

The Yippies spent the majority of 1968 planning their own contrasting Festival of Life in Chicago at the same time. Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley rejected numerous permit applications from the Yippies in an attempt to thwart the hippie invasion of the city, but it was futile.

After months of preparation, the Anti-war Movement, the Student Movement and the counterculture descended upon Chicago. When the convention convened on August 25, 1968, protestors lined the streets shouting and chanting their dissatisfaction with the failing war and the state of the Democratic party. Hoffman, who had been inspired by Marshall McLuhan’s society-altering decree of the “medium is the message”[10] chose to take every avenue possible to push the Yippie fantasy in front of the cameras. Hoffman and Rubin planned multiple forms of radical theatrics for their week in Chicago. One of these was the creation of the first protest T-shirts. The Yippie! Logo, which incorporated bold linework and psychedelic colouring, was easily transferable from posters to T-shirts. Hoffman believed that the brighter colours would draw more attention on camera.[11]

Background: Yippie protestors being arrested at the DNC. The protestor on the right, possibly Jerry Rubin, is seen wearing a Yippie! T-shirt and helmet with the official logo.

Another act of radical theatrics presented by the Yippie leaders was a pig named Pigasus, whom they intended to run for president in place of Senator Hubert Humphrey.[12] On the Thursday morning before the convention had even begun, Hoffman, Rubin, five other Yippie leaders and the pig were arrested. This group would later be known as the Chicago 7. However, this did not deter the rest of the protestors.

Pigasus being presented at the DNC, 1968

Protestors carry a banner promoting Pigasus for president, 1968.

As nighttime fell, Chicago police attempted to forcibly remove the fifteen thousand hippies that had set up camp in Lincoln Park, but they were unsuccessful. The remaining four days of the Democratic National Convention resulted in a highly intense atmosphere both inside and outside the International Amphitheatre.

September 1968 marked a change in the tide for the anti-war movement and the counterculture of the 1960s. The overwhelming feeling of unifying love that hippies had emphasized had resulted in the failure to stop the war in Vietnam and a highly sensationalized trial of the Chicago 7. The drug scene of Haight Ashbury and Greenwich Village was soon overrun with methamphetamine and crack cocaine.[13]

Hippie culture was able to sustain long enough for the Woodstock Music and Art Festival in 1969, where Woodstock tees were sold, but decreased considerably in the years following. Entering into the 1970s, T-shirts and hippie culture had become mainstream. The protest T-shirt would become a symbol of a bygone era. Disheartened and jaded, protest movements soon had to resort to violence in the name of peace.

Woodstock Music and Art Fair T-shirt. 1969.

Woodstock Music and Art Fair T-shirt. 1969.

Continue: The 1970s

Previous: A Brief History of the T-shirt

Background: Woodstock Music and Art Festival, 1969.

Notes

[6] Nieder, Alison A. Guetta, Guetta. Vintage T-Shirts. Pg. 12

[7] Young, Ralph. Dissent: The History of an American Idea. Pg. 471

[8] Pearso, Craig J. Radical Theatrics. Pg. 60

[9] Haight-Ashbury held the first “Be-In” in January 14, 1967. The event was replicated on March 26 in Central Park, New York City. Goldberg, Danny. In Search of the Lost Chord: 1967 and the Hippie Idea. Pg. 322-323

Images and Media

Navigation signs on a tree at the Woodstock Music and Art Festival, 1969. Cosgrove, Ben. “Peace, Love, Music and Mud: LIFE at Woodstock” life.com. Accessed Dec 2020.

Kellogg’s advertisement featuring a little boy, 1964. LIFE Magazine, Vol. 57, No. 9. 28 Aug, 1964. Courtesy of Google x LIFE Magazine.

Fruit of the Loom advertisement, 1968. LIFE Magazine, Vol. 65, No. 23. 6 Dec, 1968. Courtesy of Google x LIFE Magazine.

Freedom Summer volunteers, 1964. "50 Years Ago, Students Fought For Black Rights During ‘Freedom Summer’” NPR.org. Published 23 June, 2014. Accessed Dec 2020. https://www.npr.org/2014/06/23/324879867/50-years-ago-students-fought-for-black-rights-during-freedom-summer

Mario Savio speaking on top of police car. Steve Marcus, Courtesy of UC Berkeley, The Bancroft Library.

Jack Weinberg inside police car. Steve Marcus, Courtesy of UC Berkeley, The Bancroft Library

Footage of Operation Rolling Thunder. “This Major Military Operation Ignited the Vietnam War” The Smithsonian Channel. Published 18 Jan, 2018. Accessed Jan 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rbv2RCsasq8&t=1s&ab_channel=SmithsonianChannel

Peggy Caserta and Bobby Boles. Evans, Greg. “Peggy Caserta, Janis Joplin’s Love Comes Clean for Real.” Vulture Magazine. Published 2 Aug, 2018. Accessed Jan 2021.

Young couple walk the streets of Haight-Ashbury. Rothman, Lily. Liz Ronk. “See How the Peace Sign Spread in the 1960s.” time.com. Published 6 Sept, 2017. Accessed Dec 2020.

Protestors clash with Chicago Police at the Democratic National Convention, Aug 1968. Rothman, Lily. Liz Ronk. “See Vivid Colour Photos from the Democratic Convention Protests.” time.com. Published 27 July, 2016. Accessed Dec 2020.

Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin at the New York Stock Exchange following their act of theatrical protest, Aug 24, 1967. Bouissoneault, Lorraine. “How the New York Stock Exchange Gave Abbie Hoffman his Start in Guerilla Theatre.” Smithsonian Magazine. Published 24 Aug, 2017. Accessed Dec 2020.

Yippie poster advertising the Festival of Life, 1968. “Chicago ‘68: A Chronology” chicago68.com. Accessed Jan 2021. http://chicago68.com/c68chron.html

Yippie protesters being arrested at the DNC, 1968. Rothman, Lily. Liz Ronk. “See Unpublished Protest Photos from the 1968 Democratic Convention” life.com. Accessed Nov 2020. https://www.life.com/history/unpublished-protest-photos-dnc-1968/

Pigasus being presented at the DNC, 1968. Waxman, Olivia B. “'Violence Was Inevitable’: How 7 Key Players Remember the Chaos of 1968’s Democratic National Convention Protests.” time.com. Published 28 Aug, 2018. Accessed Dec 2020.

Protestors carry a banner promoting Pigasus for president, 1968. Waxman, Olivia B. “'Violence Was Inevitable’: How 7 Key Players Remember the Chaos of 1968’s Democratic National Convention Protests.” time.com. Published 28 Aug, 2018. Accessed Dec 2020.

Woodstock Music and Art Festival, 1969. Cosgrove, Ben. “Peace, Love, Music and Mud: LIFE at Woodstock” life.com. Accessed Dec, 2020.

Woodstock Music and Art Fair t-shirt. 1969. From the Collections of the National Museum of American History. ID No. 2008.0070.01. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1339853

Woodstock Music and Art Fair t-shirt. 1969. From the collection of the National Museum of American History. ID No. 1994.0250.002. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_882456